Notes from my Journal

April 6

I am in between a state of reluctance and anticipation. I can “hear” the new work better than I can understand it, something about mountains, fires, sexuality and the dark pounding of the heart.

March 31

March 31

“What is the relationship between artists and their work?” a friend asks.

I can only speak of my landscape – to economize my life so that I am available. Not as an act of abstinence or poverty, instead, of allowing. When my life is work centered, all else falls off. I am at the essence of my life. The choice is time, energy and clarity. The rest – family, friends, fun – falls into place naturally.

Being available is an act of love I give myself, for here is where my spirit lives. As I go out in my work, it is all me, and at the same time, not me. When my work connects with others, my face becomes many faces, both anonymous and personal, both unrecognizable and identifiable.

The risk of art is to be at the edge of selfishness, which seems to be vanity, but is not. Vanity keeps me separate and elevated from others. Art grovels in the same mud, but ascends.

For today, I ask what my work needs and thereby know how to live my life. Letting the non-essentials go, I keep the treasures. The rest flows from me like fall leaves tossed on the river stream, riding the current happily away from me. The love I put into my work is the same that pours into my life, family, and community. A source that renews itself continually.

October 9

The string qua rtet continues to fall into shape, and the work is exciting. The previous agony was pressure during the most vulnerable stages of composing, of gathering the raw material together, finding tiny bits of flesh, atoms or protoplasm. The stuff of creation is a delicate process, full of uncertainty and patience. It is a time when I am open to outside fears and pressures.

rtet continues to fall into shape, and the work is exciting. The previous agony was pressure during the most vulnerable stages of composing, of gathering the raw material together, finding tiny bits of flesh, atoms or protoplasm. The stuff of creation is a delicate process, full of uncertainty and patience. It is a time when I am open to outside fears and pressures.

The first section is almost completely mapped out. The rhythm tears along, bumping into sounds that are both unexpected and comfortable. I spin through reams of material, yet it is all connected somehow; tense, pressured, chased, inescapable, and swept away. I stitch together the fabric of the piece carefully, paying great attention to the transitions. The directions surprise the ear, and are, somehow, just right. The new shape of the piece pleases me, and has released the music inside. Unbelievable.

Excerpted from Let Your Heart Be Broken, Life and Music from a Classical Composer by Tina Davidson. © Tina Davidson, 2022

Drawings by Tina Davidson: Orb #1, charcoal and water color, Mysterium, colored pencil

Listen:

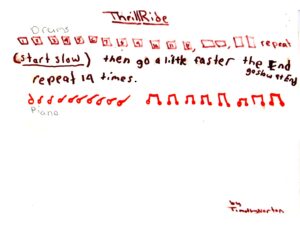

Reading music or symbols, is such a difficult process – the eyes see, the mind decodes and sends a message to the fingers, the ear hears – all the tactile, auditory, sensory abilities working together – and if one those misfires, confusion is overwhelming.

Reading music or symbols, is such a difficult process – the eyes see, the mind decodes and sends a message to the fingers, the ear hears – all the tactile, auditory, sensory abilities working together – and if one those misfires, confusion is overwhelming. Most importantly, I give them opportunities to experience and claim their own creativity. They are constantly composing music, either at home or in their lesson, notating it as they please. And several times a year, I gather them together in informal settings to perform and celebrate their efforts.

Most importantly, I give them opportunities to experience and claim their own creativity. They are constantly composing music, either at home or in their lesson, notating it as they please. And several times a year, I gather them together in informal settings to perform and celebrate their efforts. A few days up at the Charles Ives Center for the Performing Arts gives me relief. I am in residence with musician, composer, and maverick

A few days up at the Charles Ives Center for the Performing Arts gives me relief. I am in residence with musician, composer, and maverick  piece is a voyage of technical manipulations involving tape delay and difference tones – those haunting resonances that appear when certain pitches rub against each other.

piece is a voyage of technical manipulations involving tape delay and difference tones – those haunting resonances that appear when certain pitches rub against each other. My three-year residency in Delaware is winding down. We sit in meetings and talk about outcomes or measurable results of my work in community settings.

My three-year residency in Delaware is winding down. We sit in meetings and talk about outcomes or measurable results of my work in community settings. because I trust it will take root in some strange and unimagined way, in its own time. I teach as an act of faith; a spiritual practice. I get up every day, and do it. “Here,” I say, “this is what I have for you today.”

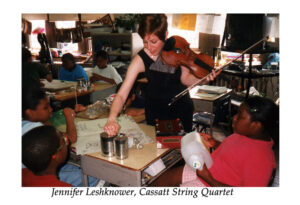

because I trust it will take root in some strange and unimagined way, in its own time. I teach as an act of faith; a spiritual practice. I get up every day, and do it. “Here,” I say, “this is what I have for you today.” Timothy stands close to me. When I move, he moves. He waits for me to play his piece with him and follows me like a shadow around the room.

Timothy stands close to me. When I move, he moves. He waits for me to play his piece with him and follows me like a shadow around the room. have no composition. I stall, thinking.

have no composition. I stall, thinking.