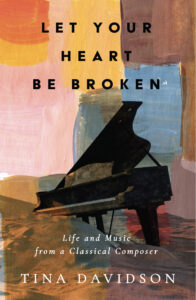

My memoir, Let Your Heart Be Broken, was recently published. Never did I imagine it would take so much work to launch and follow it through. Nor did I realize that a work in words would receive such a different response than a work in notes.

In the music world, a new piece is premiered after working with the performers in rehearsals. We confer about tempos, do a last bit of editing, talk about the musical heart of the piece and how to express it. At the performance, I introduce the work to the audience, or do a pre-concert presentation. But mostly, I am in the audience, listening. I stand for the applause, usually from my seat, or bound up to the stage for a quick bow. During the intermission and after the concert, a few audience members warmly clasp my hands. But most of them dodge around me. Did they not like my work? Or is it too vulnerable to express an opinion face to face?

In the music world, a new piece is premiered after working with the performers in rehearsals. We confer about tempos, do a last bit of editing, talk about the musical heart of the piece and how to express it. At the performance, I introduce the work to the audience, or do a pre-concert presentation. But mostly, I am in the audience, listening. I stand for the applause, usually from my seat, or bound up to the stage for a quick bow. During the intermission and after the concert, a few audience members warmly clasp my hands. But most of them dodge around me. Did they not like my work? Or is it too vulnerable to express an opinion face to face?

After the editing and revisions are done, the book is published with a flurry of press releases,  podcasts, interviews, and book tours. I get emails, messages or posts from readers, sometimes several over a week, letting me know they are halfway through, almost done, they couldn’t put it down until 4 AM. It reads like a thriller, has a musical lilt, they resonated with my words. I have introduced them to contemporary music, articulated something about composing andmy deep relationship to sound – I have put words to an art form that is generally wordless. They feel let in.

podcasts, interviews, and book tours. I get emails, messages or posts from readers, sometimes several over a week, letting me know they are halfway through, almost done, they couldn’t put it down until 4 AM. It reads like a thriller, has a musical lilt, they resonated with my words. I have introduced them to contemporary music, articulated something about composing andmy deep relationship to sound – I have put words to an art form that is generally wordless. They feel let in.

What a difference between the music world and the literary world! A live performance, or a release of CD’s will get a review or two. One can track how many listeners on Spotify or Apple Music, but never hear personally from any of them. On the other hand, my memoir not only gets reviews from critics and bloggers, but also from dozens of readers on Amazon and Goodreads. Bookstagrammers (I know! It is a word!) post their reviews to hundreds Instagram followers.

Readers are involved and connected. Listeners are mute. What is this about? Of course, there is a gap between the eye and the ear, the visual and aural. Sound is not translatable into words – that is part of its beauty. But still it doesn’t account for the lack of audience response. I wonder if it is a difference between public and private, and historical and current.

Books are read in the safety of one’s home, perched on a chair, on a couch or in bed – buffeted by cushions or nestled under a blanket, warm and comfortable. The subjects are about us – relatable – about our growing understanding of the world seen through a contemporary lens. The opposite is true in the music world. Presented in a large concert hall, music is heard in a thigh-to-thigh seating with strangers. The artists are virtuosos, highly esteemed for their performing abilities. The works they perform are primarily historical, often hundreds years old, and referred to as masterpieces. Contemporary music – our living culture – is not performed with any regularity.

performing abilities. The works they perform are primarily historical, often hundreds years old, and referred to as masterpieces. Contemporary music – our living culture – is not performed with any regularity.

Music is listened to at home, but the response is divided between popular and classical music. Taylor Swift, for example, writes music that evokes a feeling of intimacy between herself and her audience. Her fans are avidly vocal about her and hotly analyze her lyrics on line. And classical music? Honestly, I have no idea. I could not find any discussions about classical or contemporary music that included even a moderate audience.

The differences between the literary and music world are dramatic, and while the effect is up to some interpretation, my experience is of readers expressing their opinion and connecting with my work. They exude a sense of ownership, even belonging. I feel the barrier between myself and them relax, even removed. The experience is no longer mine but theirs, and in that exchange is a freedom. They are now peers, and the intimacy of the exchange is personal on both ends.

Having tasted this fruit, I want more of this. I especially want this for my music world.

In college, I took up cello in addition to studying composition and piano. At times I studied with Michael Finkle, who, mustached, quirky, was full of joy. Up in a large room on the third floor of the music building we gathered weekly to play cello quartets and octets late into the evening. As a night cap, he turned off the lights and we improvised in the dark.

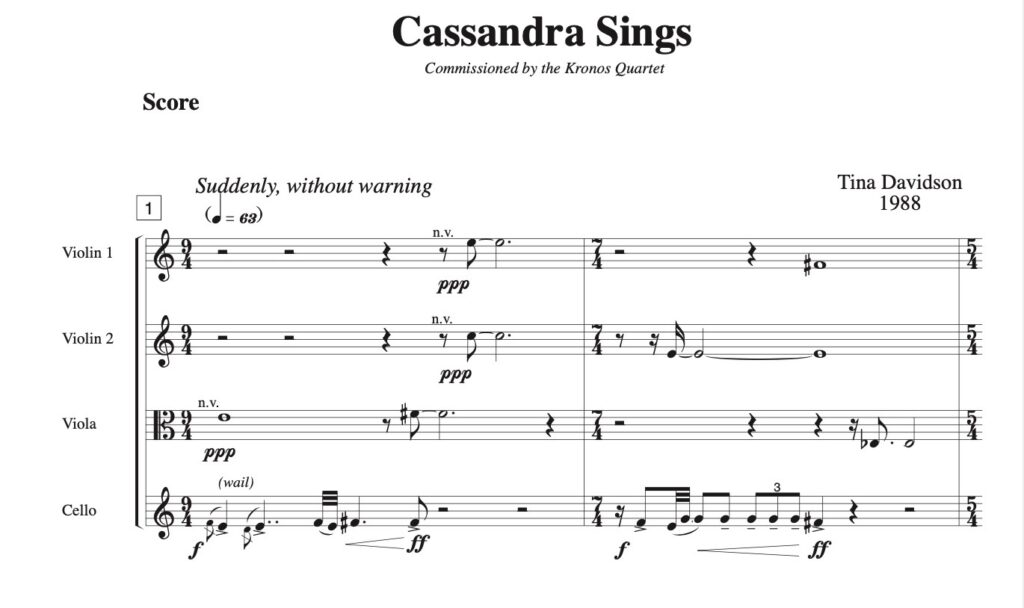

In college, I took up cello in addition to studying composition and piano. At times I studied with Michael Finkle, who, mustached, quirky, was full of joy. Up in a large room on the third floor of the music building we gathered weekly to play cello quartets and octets late into the evening. As a night cap, he turned off the lights and we improvised in the dark. It was Anna Cholakian, the cellist of the Cassatt Quartet, who cemented my love for cello. Delicate and long-haired dark hair, she played with a intensity and passion that belied her small frame. Listen to her play the opening of my string quartet, Cassandra Sings.

It was Anna Cholakian, the cellist of the Cassatt Quartet, who cemented my love for cello. Delicate and long-haired dark hair, she played with a intensity and passion that belied her small frame. Listen to her play the opening of my string quartet, Cassandra Sings.