Timothy stands close to me. When I move, he moves. He waits for me to play his piece with him and follows me like a shadow around the room.

Timothy stands close to me. When I move, he moves. He waits for me to play his piece with him and follows me like a shadow around the room.

I help Shante with her instrument, calm Ferron down so he can concentrate, and get sidelined by Brandi and Terrell. They work on a piece for two desks and their hands. Experimenting with fingers, palms, and fists, they make sounds on the wooden tops. I step back and almost fall over Timothy; he is patient.

Jake and Michael struggle with their invented notation. Jake’s faces contorts, he cannot figure out how to write his rhythm down. We put words to the melody, and suddenly he claps it with ease.

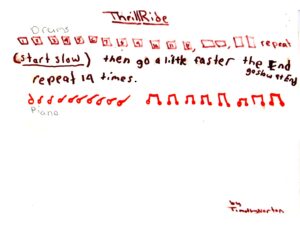

Timothy pushes me towards the piano and I grab a drum. His piece, Thrill Ride, is carefully notated in tiny print. Only he knows what it means, but he has taught me. He begins to play, his long fingers curving around the complicated chords. A dreamy look comes over his face.

“How will I know when to stop?” I press him. He continues to play, immersed in his own sound world. (McMichael Elementary School)

∗∗∗∗∗

Michael’s eyes are full of tears. His small body slumps in the chair. “It’s not fair! I want to work with the cellist.” Tears splash down his face. I study him for a moment, then settle down beside him.

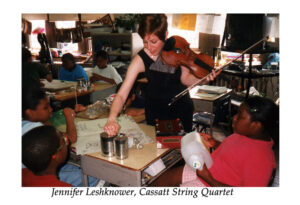

Michael and two other boys were out of the room recording the rap lyrics to the song the fifth grade class had written. During their absence, the rest of the class completed their graphically notated pieces about Homer’s Odyssey. Today, the Cassatt String Quartet joins my residency. Each group will collaborate with a member of the ensemble. The three boys have no composition. I stall, thinking.

have no composition. I stall, thinking.

“What if you write a new piece for all of the string players right now?” I suggest. Michael runs for the markers and newsprint. Working quickly, the boys write a piece they call Rough Riders from Lotus Town. They fight briefly about how to notate the motorcycle sound.

After a discussion, the Quartet plays the piece for the class. Michael leans into me, smiling. “They played my piece pretty good!” he concedes. (Nebinger Elementary School)

Excerpted from Let Your Heart Be Broken, Life and Music from a Classical Composer © Tina Davidson, 2022.

Listen: Celestial Turnings, string orchestra: excerpt

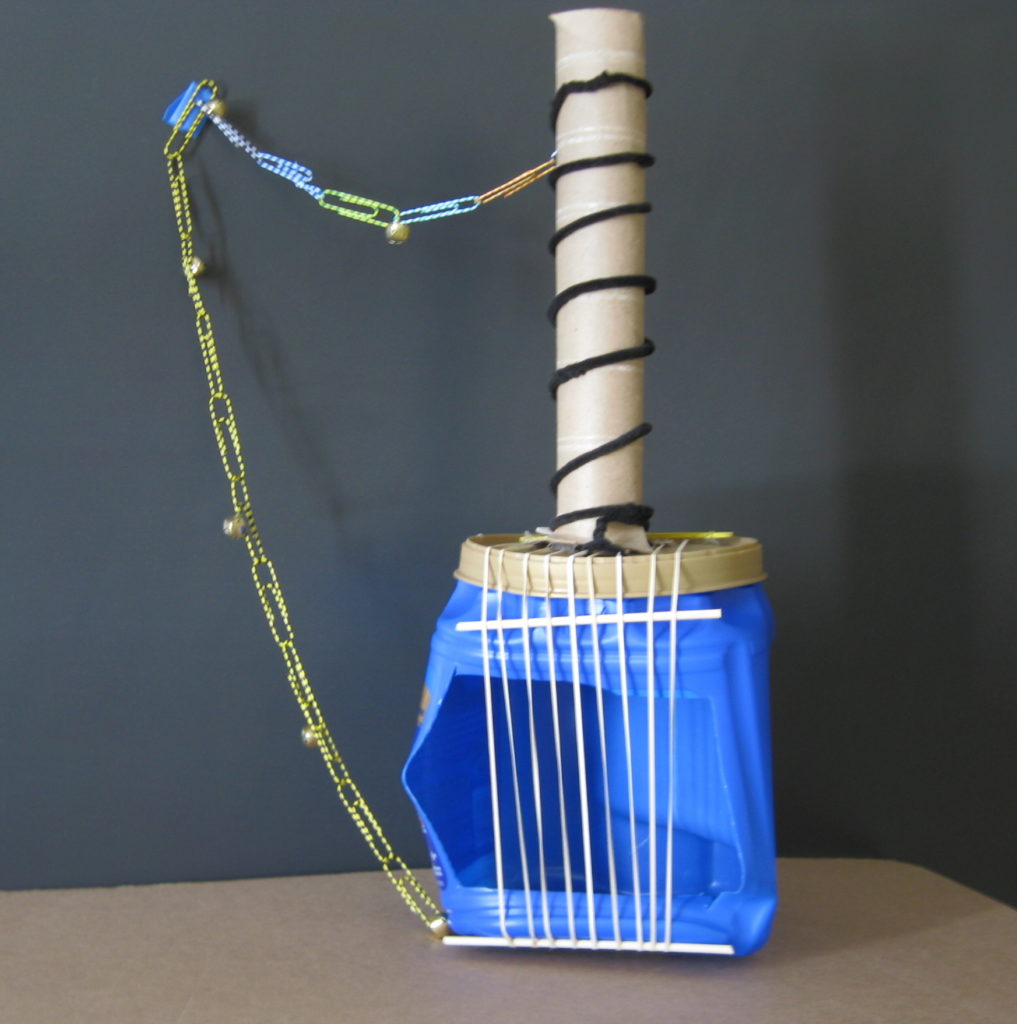

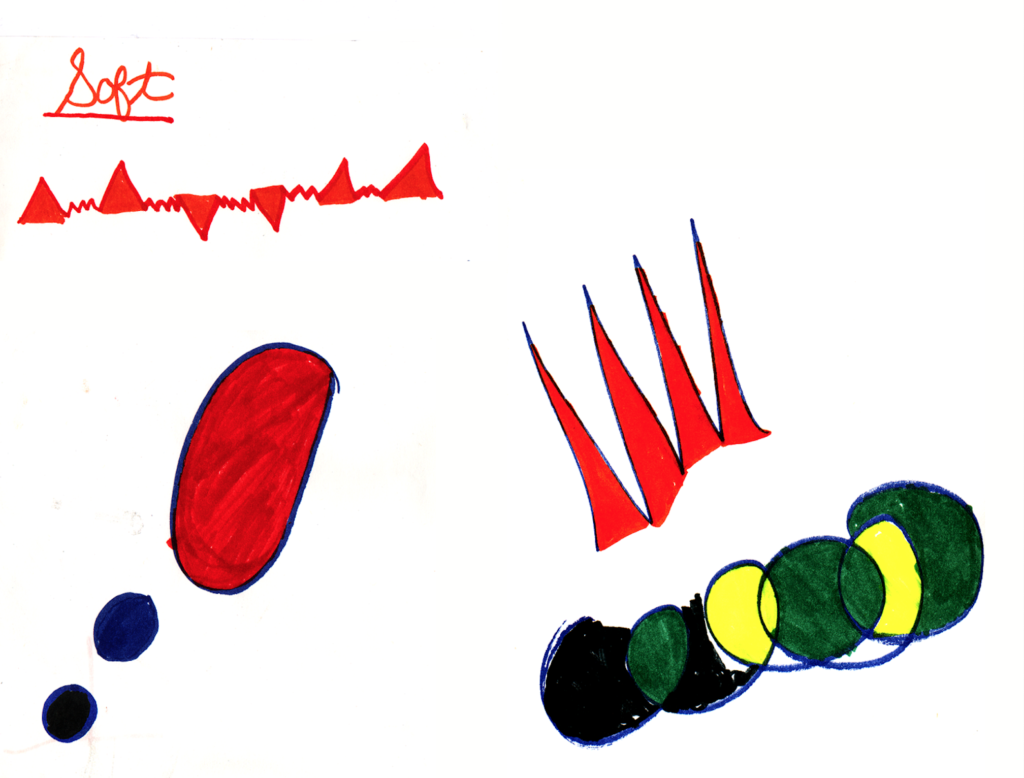

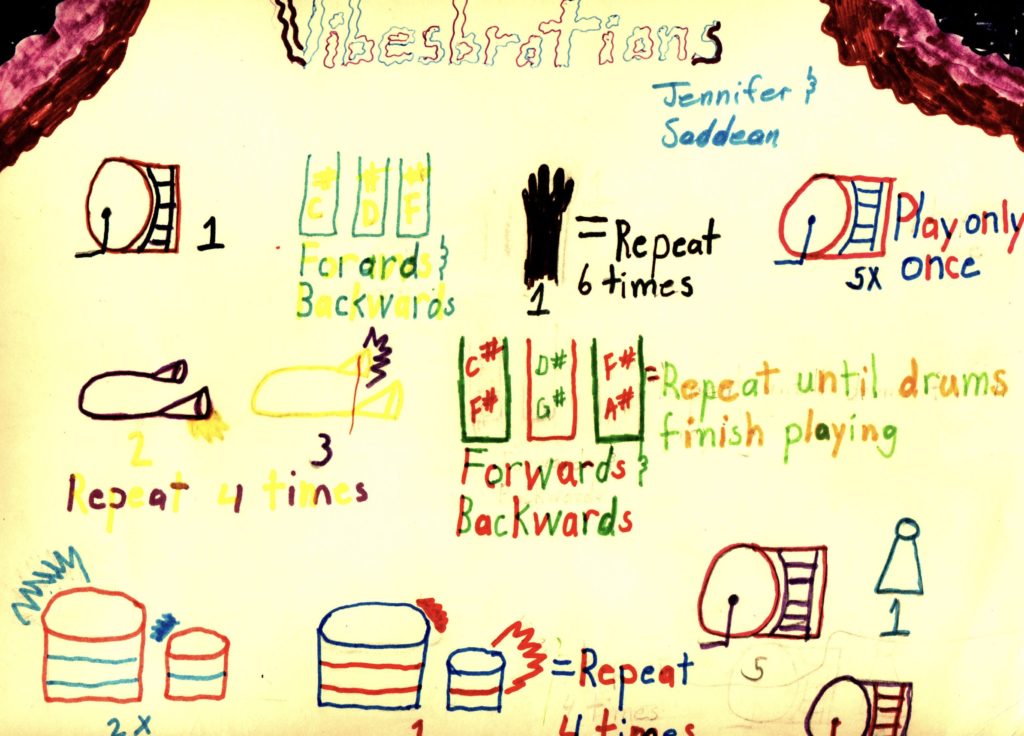

Tina Davidson created Young Composers program to teach students to compose their own music through instrument building, graphic and invented notation. Designed to enhance self-esteem and reinforce achievement through alternative measures of expression, the course culminates with a performance of the students’ compositions.

Listen: Render, for string quartet was commissioned for the Cassatt String Quartet

Listen: Render, for string quartet was commissioned for the Cassatt String Quartet