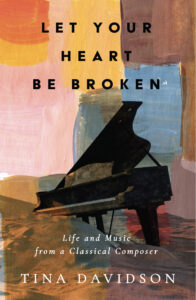

I am perplexed. Since my memoir, Let Your Heart Be Broken, has been published, I have had a couple of reviews complaining that I didn’t write about my music in a “substantive way.”

I am perplexed. Since my memoir, Let Your Heart Be Broken, has been published, I have had a couple of reviews complaining that I didn’t write about my music in a “substantive way.”

“We get a strong sense of the composer’s moods and environments as she creates her art, but nothing of the mechanics or matters of style.”

The ‘mechanics’ of composing – huh. I am not completely sure what the reviewers are wanting. Perhaps how I choose chords or notes? Or exactly how I create metric modulations or my musical form? And as to ‘matters of style’ – for the life of me, I am clueless; it is not what I consider as I compose.

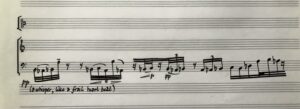

In my memoir, I write about my composing process. Not the actual putting the pencil on the page, but what is in my mind as I compose, what I am interested in both sonically and emotionally, and how it pertains to where I am in my life. I also write about what I am intellectually interested in at the moment – where does pitch begin, how do I create a musical situation where the notes magnetically move themselves, or what happens to an exhausting rhythmic sequence – at the moment before it falls to the ground.

Is this not enough? Am I still not writing about the ‘mechanics’ of composing?

I came to composing through the portal of playing the piano since I was five years old. I learned harmonic changes by ear; they had no name, instead were imprinted on my bones. I studied music theory and harmony only after college and never much believed in it – it seemed to apply only to classical music written long ago (counterpoint, on the other hand, is eternally useful). These studies made me wonder whether Beethoven knew what he was composing in a step by step way, or was he so in the fullness of the moment that the music just came out of him?

There is so much of the creative process, for me, that is an accumulation of years of practice,  information and experience. Thus the fingers that grip the pencil over the music paper know instinctively what to do – or, at the very least, start to move towards that end. It is no longer an intellectual process for me, but an intuitive one that is very difficult to parse out, give meaning to, or even teach.

information and experience. Thus the fingers that grip the pencil over the music paper know instinctively what to do – or, at the very least, start to move towards that end. It is no longer an intellectual process for me, but an intuitive one that is very difficult to parse out, give meaning to, or even teach.

When students ask me how to develop a piece, or make transitions between one section and another so that there is a seamless flow, I throw out a couple of ideas; tension, resolution, gravity, friction. But these are only words compared to the practice of doing it again and again until they have solved the problem for themselves. We sit and listen to one of their pieces, sniffing out how the phrase fell flat, or the melody didn’t lift. I am both coach and cheering section, my job is not to fix as much as encourage students to move forward.

Are the mechanics, then, irrelevant? I am undecided. We all want to understand how something is created on a deeper level. To name it, or give words to it, is another entrance into the work from a different angle. I totally support demystifying the artistic endeavor. Mechanics, however, just seem to add another layer to confuse and distance listeners.

Oh! I wish could explain the mechanics of my composing process the way my art teacher tries to get me to draw realistically. I apply all the perspective and foreshortening, the color theory and the idea of value – but when she takes up my brush to show me, her brush is alive in a way that neither of us can articulate.

Oh! I wish could explain the mechanics of my composing process the way my art teacher tries to get me to draw realistically. I apply all the perspective and foreshortening, the color theory and the idea of value – but when she takes up my brush to show me, her brush is alive in a way that neither of us can articulate.

stiffening up the whole hand so it can bear the weight of the arm, or even engaging the back; soft sounds take more muscle restraint. Recently at a concert, I saw a brilliant young pianist stab the keyboard with stiffened fingers to create a percussive depth of sound, then bending her back, using loose wrists, her fingers whispered a soft rapid phrase.

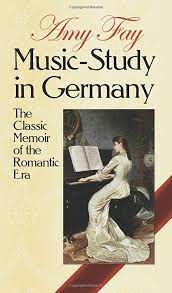

stiffening up the whole hand so it can bear the weight of the arm, or even engaging the back; soft sounds take more muscle restraint. Recently at a concert, I saw a brilliant young pianist stab the keyboard with stiffened fingers to create a percussive depth of sound, then bending her back, using loose wrists, her fingers whispered a soft rapid phrase. Piano technique has a long and rich history. During Bach and Mozart’s time, the keyboards were light to the touch. Performers used what was know as the “finger action” school, where the arms were relatively fixed, and the fingers skittered along. As the piano evolved with a wider range of volume, the touch became heavier. Pianists and composers such as Chopin and Liszt began to use the weight of the arm, playing with a supple wrist; this became known as the “arm weight” school of technique. I love the description that

Piano technique has a long and rich history. During Bach and Mozart’s time, the keyboards were light to the touch. Performers used what was know as the “finger action” school, where the arms were relatively fixed, and the fingers skittered along. As the piano evolved with a wider range of volume, the touch became heavier. Pianists and composers such as Chopin and Liszt began to use the weight of the arm, playing with a supple wrist; this became known as the “arm weight” school of technique. I love the description that  the way the yarn wound around my right index finger, slipped it in and out of clicking needles. Recently, I became fascinated with the various weights and textures of wool, and then, the consummate deliciousness of cashmere, thin, durable and much too expensive to buy. I found old cashmere sweaters at the thrift shop, and slowly undoing the side seams, I unraveled the yarn into glowing balls. I was, I confess, obsessed with the ease of this wealth of yarn and I made fingerless gloves, hats, scarves, and finally large cashmere blankets until my family begged me to stop.

the way the yarn wound around my right index finger, slipped it in and out of clicking needles. Recently, I became fascinated with the various weights and textures of wool, and then, the consummate deliciousness of cashmere, thin, durable and much too expensive to buy. I found old cashmere sweaters at the thrift shop, and slowly undoing the side seams, I unraveled the yarn into glowing balls. I was, I confess, obsessed with the ease of this wealth of yarn and I made fingerless gloves, hats, scarves, and finally large cashmere blankets until my family begged me to stop.

.

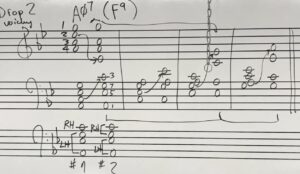

. performance, harmony, counterpoint, set-theory, analysis and orchestration before pencil hits the paper. The canon maintains that understanding music history is an essential, and without it the artist gropes in the dark in a vain attempt to reinvent the wheel. The canon implies an order – one must do A before B. It reinforces that personal creativity is not trustworthy unless it is in an old container: it is not credible without context. In other words, one must be coupled to the past to make authentic, groundbreaking art.

performance, harmony, counterpoint, set-theory, analysis and orchestration before pencil hits the paper. The canon maintains that understanding music history is an essential, and without it the artist gropes in the dark in a vain attempt to reinvent the wheel. The canon implies an order – one must do A before B. It reinforces that personal creativity is not trustworthy unless it is in an old container: it is not credible without context. In other words, one must be coupled to the past to make authentic, groundbreaking art. a personal ownership that grows out of doing. I support experiencing writing music before too much comparison. In the initial stage, I want everyone to compose the way they painted in kindergarten. Hardly knowing how to hold a paint brush, they work with abandon and in full confidence of their creative abilities.

a personal ownership that grows out of doing. I support experiencing writing music before too much comparison. In the initial stage, I want everyone to compose the way they painted in kindergarten. Hardly knowing how to hold a paint brush, they work with abandon and in full confidence of their creative abilities.