I see Henry* at the conference, a wonderful composer and someone who has championed the field of new music as well as other composers. I take his elbow warmly.

Smiling, Henry turns to me from his conversation with a tall man who’s name I don’t catch. His friend interrupts our greeting. “I have to finish this conversation,” he says, and animatedly continues his long story about a job application as a composer that had not gone well.

“And then,” he finally finishes, “they hired a woman!” He pauses and names the composer. “This job was a fit perfect for my talents. Instead, they hired a woman.”

Henry knows her. “She is a wonderful composer,” he counters, “and she will be fabulous at this job.”

His friend shakes his head. All jobs are going to minority and gender diverse candidates; white men are being pushed out. I am flooded with thoughts.

I began my composing career in a music world governed by the idea of excellence – that the best candidate should get the job, the commission, or the performance. The catch, however, was who was determining this “excellence” and what the criteria was. I quickly learned that “excellence” included which school you attended, who you studied with, what kind of music you were composing, and finally, gender and race.

Fortunately, we are in a different time. Now, music institutions know that to survive they must find new connections with their audiences, as well as represent the broader community. Part of that work is to offer opportunities to minority and gender diverse composers and support those who have been hidden in the shadows.

But there is something else. Historically there have been no women composers as well known as Mozart, Beethoven and Brahms. For many reasons women were not encouraged or often ignored. But more importantly, they didn’t have opportunities to hear their music – a vital link to their growth and maturity as a composer.

Music doesn’t fully exist independent of performance. Unlike literature or art, music is incomplete until it goes under the fingers of a performer, who wrestle with translating and bringing it into life. Even then, the work is not fully realized until it is in front of an audience. Something magical happens to the work in this communication, this transfer to the ears of the listener. And it is where I learn, evaluate, and move onto the next project with increased wisdom. Without the performance of my work, my progress is hindered and only half completed.

In truth, there are always winners and losers in the face of opportunity. The pendulum sways back and forth. I have lived through the shift of dominance of university composers (mostly white men), the push for representation of women, the activation of composers in community settings, and now the inclusion of DEI. I am thrilled at where we are, and where we are moving to. This music field – this thing I love, will be greatly enhanced.

I applaud these opportunities to marginalized composers to speak, hear and learn. As their voices join with others, we cultivate a rich, diverse artistic field which will, over time, speak to and for all of us.

- Not his real name.

There, right there is the magic – that lift, as if you were about to fly. The upward motion pulls at gravity. I am a kayak, rushing downstream only to hit a rock. As I fly in the air, the suspension seems longer than possible; my heart stops beating for a endlessly long moment – time is distorted.

There, right there is the magic – that lift, as if you were about to fly. The upward motion pulls at gravity. I am a kayak, rushing downstream only to hit a rock. As I fly in the air, the suspension seems longer than possible; my heart stops beating for a endlessly long moment – time is distorted. My mother was the first feminist in the family. She read Gloria Steinem, Kate Millett, Germaine Greer and Betty Friedan. She taught women’s studies and went to on countless marches. True, she often spat and lectured. A professor at the State College in Oneonta, mother of five, she knew the limits of her salary and position. She had valid grievances and was angry.

My mother was the first feminist in the family. She read Gloria Steinem, Kate Millett, Germaine Greer and Betty Friedan. She taught women’s studies and went to on countless marches. True, she often spat and lectured. A professor at the State College in Oneonta, mother of five, she knew the limits of her salary and position. She had valid grievances and was angry. the plates. We waited to see what emerged. Colors bloomed several days later, a brilliant white and a poisonous looking orange – a world invisible – existing only when it was allowed to grow by itself.

the plates. We waited to see what emerged. Colors bloomed several days later, a brilliant white and a poisonous looking orange – a world invisible – existing only when it was allowed to grow by itself. of the Greek prophetess who was never listened to or believed, and my hope for better times in the future. Women Dreaming, for mixed ensemble and piano, was my continued dreaming of possibilities. River of Love, River of Light, a seven movement choral piece, was my understanding of the female face of God.

of the Greek prophetess who was never listened to or believed, and my hope for better times in the future. Women Dreaming, for mixed ensemble and piano, was my continued dreaming of possibilities. River of Love, River of Light, a seven movement choral piece, was my understanding of the female face of God. In the music world, a new piece is premiered after working with the performers in rehearsals. We confer about tempos, do a last bit of editing, talk about the musical heart of the piece and how to express it. At the performance, I introduce the work to the audience, or do a pre-concert presentation. But mostly, I am in the audience, listening. I stand for the applause, usually from my seat, or bound up to the stage for a quick bow. During the intermission and after the concert, a few audience members warmly clasp my hands. But most of them dodge around me. Did they not like my work? Or is it too vulnerable to express an opinion face to face?

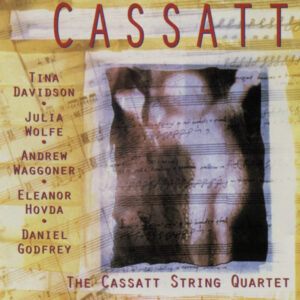

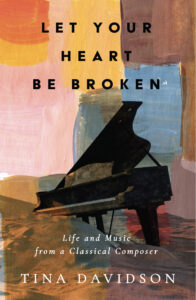

In the music world, a new piece is premiered after working with the performers in rehearsals. We confer about tempos, do a last bit of editing, talk about the musical heart of the piece and how to express it. At the performance, I introduce the work to the audience, or do a pre-concert presentation. But mostly, I am in the audience, listening. I stand for the applause, usually from my seat, or bound up to the stage for a quick bow. During the intermission and after the concert, a few audience members warmly clasp my hands. But most of them dodge around me. Did they not like my work? Or is it too vulnerable to express an opinion face to face? podcasts, interviews, and book tours. I get emails, messages or posts from readers, sometimes several over a week, letting me know they are halfway through, almost done, they couldn’t put it down until 4 AM. It reads like a thriller, has a musical lilt, they resonated with my words. I have introduced them to contemporary music, articulated something about composing andmy deep relationship to sound – I have put words to an art form that is generally wordless. They feel let in.

podcasts, interviews, and book tours. I get emails, messages or posts from readers, sometimes several over a week, letting me know they are halfway through, almost done, they couldn’t put it down until 4 AM. It reads like a thriller, has a musical lilt, they resonated with my words. I have introduced them to contemporary music, articulated something about composing andmy deep relationship to sound – I have put words to an art form that is generally wordless. They feel let in. performing abilities. The works they perform are primarily historical, often hundreds years old, and referred to as masterpieces. Contemporary music – our living culture – is not performed with any regularity.

performing abilities. The works they perform are primarily historical, often hundreds years old, and referred to as masterpieces. Contemporary music – our living culture – is not performed with any regularity. suggest. I am their supporter and collaborator. They are brilliant musicians. “Just play the music!”

suggest. I am their supporter and collaborator. They are brilliant musicians. “Just play the music!” In the end, the performers collaborate with the audience – the receivers of the music. For me, it is a journey, a traveling through a sonic and emotional landscape. Because music can only experienced through time, the listener perceives the whole only with the aid of memory, a remembrance of beginning. As the performers bend over their music and the audience listens, the energy between them creates the experience.

In the end, the performers collaborate with the audience – the receivers of the music. For me, it is a journey, a traveling through a sonic and emotional landscape. Because music can only experienced through time, the listener perceives the whole only with the aid of memory, a remembrance of beginning. As the performers bend over their music and the audience listens, the energy between them creates the experience.