My world, whether in music or in my country, is dear to me.

I will not let it go without some sort of action.

The evening in my studio was beginning to darken at a recent Composer Posse gathering. Faces shone from my computer screen as fifteen composers shared information and support about their creative work. The topic of life prior to computers and notation software came up, and laughingly we recounted the times before.

I came to the field when we used India ink, vellum, with an ozalid process to print out long accordion fold scores. Others, younger than myself, began their careers when they copied out their music with pen and score paper and photocopied it.

I came to the field when we used India ink, vellum, with an ozalid process to print out long accordion fold scores. Others, younger than myself, began their careers when they copied out their music with pen and score paper and photocopied it.

“That reminds me,” Jennifer Higdon said, leaning forward with a smile, “of an amazing story.”

While in graduate school at the University of Pennsylvania, a composer colleague of hers had finally completed a large work for orchestra with only a week before the rehearsals began. He had copied his lengthy work out by hand on paper, a breath taking long process. Then with care, he copied out each individual orchestral part. A one of a kind score and parts, with no backup.

Stacked and ready to go to the copier, the composer left his work on the kitchen table. Upon waking the next morning, he was horrified to find that his little grey striped kitten had squatted on top of the music and let loose a yellow stream. The score was soaked, the inked notes melted and flowed down the page, the parts were stained and shredded. The entire project was rendered useless; a catastrophe beyond measure for any composer.

In a panic, he called up his friends. They, in turn, did something extraordinary. Each taking a portion of the piece, they re-copied the score and parts for their friend. Working full-time over a week, they hand reconstructed the orchestra piece with over thirty parts before the first rehearsal.

Thinking back on Jennifer’s story, I wonder at this display of support between artists. Working together, each completed a small part of a larger piece, reconstructing the torn, yellow stained ruin into something whole. In other words, small actions, taken together, are important.

It is, in the end, what we face in today’s political arena. Coming together as concerned citizens, we are less afraid of what is happening or what might happen if we speak out. We can be positive and also realistic; we don’t have to agree, but can always be respectful. And we never, never underestimate the power of our actions, no matter how small.

My world, whether in music or in my country, is dear to me. I will not let it go without some sort of action.

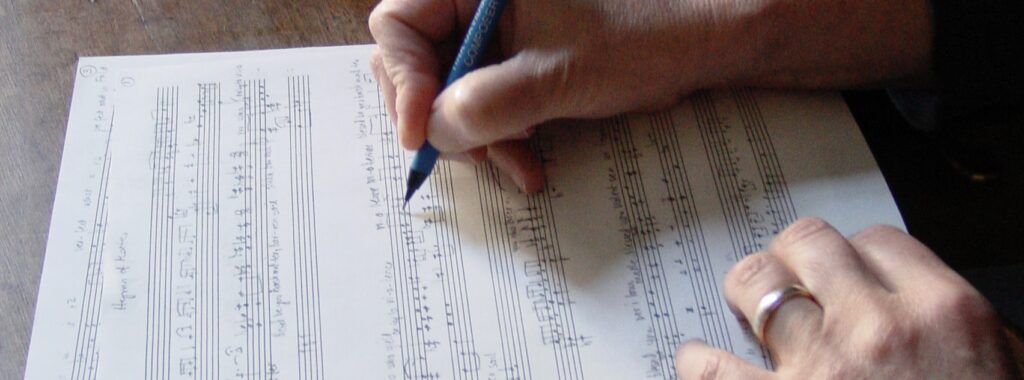

This sensitivity to touch comes from decades as a pianist; my fingertips can almost see at touch. The act of playing music on a piano is about bending the bones of my fingers – meeting music with my flesh – moving into and through to mold, bend, scoop it out of the ivories. This finger work, whether at the piano or grasping a pencil, sees and smells independently of myself.

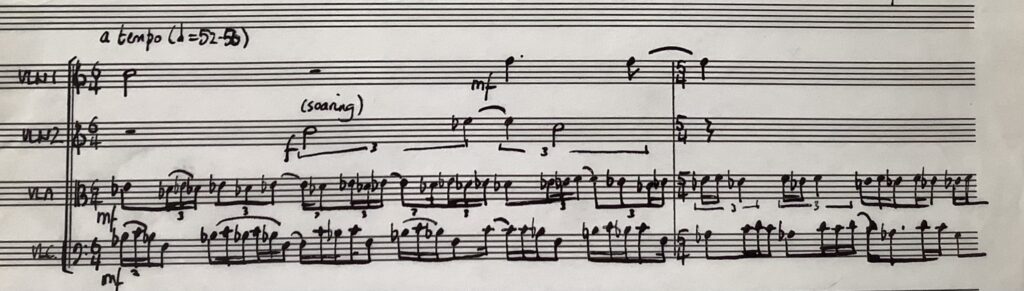

This sensitivity to touch comes from decades as a pianist; my fingertips can almost see at touch. The act of playing music on a piano is about bending the bones of my fingers – meeting music with my flesh – moving into and through to mold, bend, scoop it out of the ivories. This finger work, whether at the piano or grasping a pencil, sees and smells independently of myself. A music notation program, no matter how brilliant, is a box in which I fit my music. They are created based on classical music or even programmers’ ideas, and lag far behind living composers who challenge perceptions and create new ways of communicating music. It has to catch up to me, not the other way around.

A music notation program, no matter how brilliant, is a box in which I fit my music. They are created based on classical music or even programmers’ ideas, and lag far behind living composers who challenge perceptions and create new ways of communicating music. It has to catch up to me, not the other way around.

There are plenty of examples of badly behaved composers. Gesualdo committed a gruesome murder and mutilation of both his wife and her lover, Beethoven was famously temperamental and more than a bit abusive to his nephew, and Wagner was a fervent anti-Semite. Scriabin was a pathological narcissist who imagined himself a god and Mussorgsky was a raging, out-of-control alcoholic who idealized his addiction. Closer to home, I know many good composers I would rather not spend any time with.

There are plenty of examples of badly behaved composers. Gesualdo committed a gruesome murder and mutilation of both his wife and her lover, Beethoven was famously temperamental and more than a bit abusive to his nephew, and Wagner was a fervent anti-Semite. Scriabin was a pathological narcissist who imagined himself a god and Mussorgsky was a raging, out-of-control alcoholic who idealized his addiction. Closer to home, I know many good composers I would rather not spend any time with. “Without music, I am plain and unremarkable. I shop, eat, dally about, think foolish thoughts, peer into the mirror. I hate, I love, I sleep, I anguish—nothing special. But when focused on writing music, I am a channel, a beam of light – I am a passageway for what must come out. My entire person comes together in a pulse, condensed and absorbed. The work follows me everywhere. I hear it in the bathroom, while I am cooking, as I fall asleep. There is always this murmur, this whisper.” (page 47)

“Without music, I am plain and unremarkable. I shop, eat, dally about, think foolish thoughts, peer into the mirror. I hate, I love, I sleep, I anguish—nothing special. But when focused on writing music, I am a channel, a beam of light – I am a passageway for what must come out. My entire person comes together in a pulse, condensed and absorbed. The work follows me everywhere. I hear it in the bathroom, while I am cooking, as I fall asleep. There is always this murmur, this whisper.” (page 47) The relationship between my life, who I am and how I behave, and my work is inseparable. There is no slacking off in either regard. I am as flawed as the next person, but it is how I am accountable to and work on those flaws that matters.

The relationship between my life, who I am and how I behave, and my work is inseparable. There is no slacking off in either regard. I am as flawed as the next person, but it is how I am accountable to and work on those flaws that matters.