I am at a local concert, listening to a performance of Beethoven’s “Appassionata” Piano Sonata, No. 23. The pianist has impeccable clarity as he thunders through the tempestuous last movement. The speed  of his playing, however, distracts me. What is it about the escalating speeds in performances of musical works?

of his playing, however, distracts me. What is it about the escalating speeds in performances of musical works?

Everything is faster and faster these days. In fact, things have sped up so much that they say our brains have been reprogrammed. Being forced to use a rotary phone, taking 7 to 12 seconds to dial a number, would probably drive us crazy. Once adjusted to the current speed of our computer, slow loading of a program can be irritating, even anxiety provoking.

Physical prowess has also changed. Young athletes are bigger, faster and stronger, demonstrating a level of athleticism that was once considered beyond their years, due to a combination of better training techniques, technological advances, and specialized sports science. For example, in the 1980s and 1990s, few Olympic and professional sprinters could run a 100-meter dash in under 10 seconds. Since 2019, however, some high school athletes have been able to do so.

In other words, once a barrier is broken, it becomes a standard. A gifted athlete – or prodigy performer – creates a new marker of normal.

In other words, once a barrier is broken, it becomes a standard. A gifted athlete – or prodigy performer – creates a new marker of normal.

The classical music field reflect much of this increased speed. According to the 2018 Universal Music Group study, the recordings of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Double Violin Concerto have sped up by as much as 30% since 1961, with the 2016 recording lasting about 12 minutes compared to 17 minutes. Modern recordings, the study suggests, may be picking up the pace by about a minute per decade.

With escalating speed of performance comes an increase of technical abilities. I was up at the recent Tanglewood Contemporary Music Festival when Steve Mackey introduced his work, Physical Property. In the mid 1990s, performers struggled to master his technically difficult work. Now, he laughed, the young performers, “Ate it up like whip cream.”

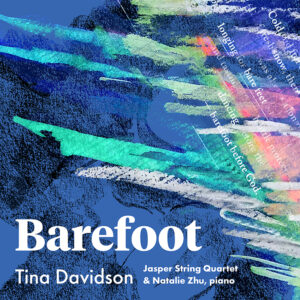

Last year, I was in rehearsals with the Jasper String Quartet and Natalie Zhu. We were preparing for the the recording of my latest album, Barefoot. The quartet were playing my difficult work beautifully; seamlessly moving through the tricky meter changes and the rambunctious middle section.

Last year, I was in rehearsals with the Jasper String Quartet and Natalie Zhu. We were preparing for the the recording of my latest album, Barefoot. The quartet were playing my difficult work beautifully; seamlessly moving through the tricky meter changes and the rambunctious middle section.

As the piece closed, we sat for a moment. “Wow,” I finally said, “You play fast!” I paused, “Can you take it slower?”

They smiled. Of course.

How fast, ultimately, can we listen, and what do we miss hearing because of speed? I love composing music that quickly twists and turns upward, or plunges downward. Hanging for a moment, breathless, it dashing off to another curve. Playing it too fast, however, flattens, even blurs the music. Sadly, we do not have instant playback to rehear, in the moment, and decipher the music that just rushed by us.

For my part, I say to my performers, slow down. Breathe. Allow the music to have more space.

There are plenty of examples of badly behaved composers. Gesualdo committed a gruesome murder and mutilation of both his wife and her lover, Beethoven was famously temperamental and more than a bit abusive to his nephew, and Wagner was a fervent anti-Semite. Scriabin was a pathological narcissist who imagined himself a god and Mussorgsky was a raging, out-of-control alcoholic who idealized his addiction. Closer to home, I know many good composers I would rather not spend any time with.

There are plenty of examples of badly behaved composers. Gesualdo committed a gruesome murder and mutilation of both his wife and her lover, Beethoven was famously temperamental and more than a bit abusive to his nephew, and Wagner was a fervent anti-Semite. Scriabin was a pathological narcissist who imagined himself a god and Mussorgsky was a raging, out-of-control alcoholic who idealized his addiction. Closer to home, I know many good composers I would rather not spend any time with. “Without music, I am plain and unremarkable. I shop, eat, dally about, think foolish thoughts, peer into the mirror. I hate, I love, I sleep, I anguish—nothing special. But when focused on writing music, I am a channel, a beam of light – I am a passageway for what must come out. My entire person comes together in a pulse, condensed and absorbed. The work follows me everywhere. I hear it in the bathroom, while I am cooking, as I fall asleep. There is always this murmur, this whisper.” (page 47)

“Without music, I am plain and unremarkable. I shop, eat, dally about, think foolish thoughts, peer into the mirror. I hate, I love, I sleep, I anguish—nothing special. But when focused on writing music, I am a channel, a beam of light – I am a passageway for what must come out. My entire person comes together in a pulse, condensed and absorbed. The work follows me everywhere. I hear it in the bathroom, while I am cooking, as I fall asleep. There is always this murmur, this whisper.” (page 47) The relationship between my life, who I am and how I behave, and my work is inseparable. There is no slacking off in either regard. I am as flawed as the next person, but it is how I am accountable to and work on those flaws that matters.

The relationship between my life, who I am and how I behave, and my work is inseparable. There is no slacking off in either regard. I am as flawed as the next person, but it is how I am accountable to and work on those flaws that matters.

I always wanted to take over the music world. I know it is a silly goal in the face of reality, but I am tired of the competition between composers, not to mention the condescension by classical music to contemporary music, or the lack of opportunities for this generation of music to flourish. So, teaming up with others, I ground my advocacy in radical inclusion. And this has enriched my life beyond measure.

I always wanted to take over the music world. I know it is a silly goal in the face of reality, but I am tired of the competition between composers, not to mention the condescension by classical music to contemporary music, or the lack of opportunities for this generation of music to flourish. So, teaming up with others, I ground my advocacy in radical inclusion. And this has enriched my life beyond measure. I sigh and drum my pencil on the blank score paper. All morning I have been procrastinating, unable to move forward in composing my next work. I am caught in the bardo of creation – between not knowing and, at the same time, sensing the direction of the piece.

I sigh and drum my pencil on the blank score paper. All morning I have been procrastinating, unable to move forward in composing my next work. I am caught in the bardo of creation – between not knowing and, at the same time, sensing the direction of the piece. My ear is always bending towards the sound strings produce when I compose. The instrument itself is an ingenuity of construction – as one plays, the open strings resound, building up a deepening of sound – like a piano’s sustaining pedal, but discrete and selective. The resonating strings respond like ghosts to a call, building up overtones and harmonics, even different tones.

My ear is always bending towards the sound strings produce when I compose. The instrument itself is an ingenuity of construction – as one plays, the open strings resound, building up a deepening of sound – like a piano’s sustaining pedal, but discrete and selective. The resonating strings respond like ghosts to a call, building up overtones and harmonics, even different tones. sound to a bare shadow of itself by playing with the wood of the bow) gets closer to what I experience in a single note or tone – an outer shell-like-flesh with a soft inner core.

sound to a bare shadow of itself by playing with the wood of the bow) gets closer to what I experience in a single note or tone – an outer shell-like-flesh with a soft inner core. , religion, education, or just being at the wrong place at the wrong time), break in through the back door or window. No matter how you get in, you are in.

, religion, education, or just being at the wrong place at the wrong time), break in through the back door or window. No matter how you get in, you are in. ars. When I got a commission from the Kronos Quartet, that and my savings allowed me to launch into being able to compose full time.

ars. When I got a commission from the Kronos Quartet, that and my savings allowed me to launch into being able to compose full time. Share your joy.

Share your joy.