Katie fidgets at the piano, and looks blankly at the music. I touch her shoulder and put my pencil on the errant note. She settles down and with much stumbling and back tracking, plays the piece. We cheer together as I hand her a sheet of stickers. She pauses long, trying to decide which one pick. I know she is taking a much-needed break from focusing. Then we start up again.

Reading music or symbols, is such a difficult process – the eyes see, the mind decodes and sends a message to the fingers, the ear hears – all the tactile, auditory, sensory abilities working together – and if one those misfires, confusion is overwhelming.

Reading music or symbols, is such a difficult process – the eyes see, the mind decodes and sends a message to the fingers, the ear hears – all the tactile, auditory, sensory abilities working together – and if one those misfires, confusion is overwhelming.

Clearly, I should say something to Katie’s parents. Her child has some sort of learning difficulty. But when I ask obliquely about how she doing in school, her mother’s face freezes. I change the subject.

In truth, it is none of my business. I am not a trained professional, and do not know what is developmental, and what is more serious. Furthermore, parents have their own path and time-table of recognizing their child’s difficulty and dealing with it.

But mostly, I don’t want to forfeit the opportunity. I have a thirty-minute window each week to spend with Katie over a few years, perhaps even as long as a ten-year-span. How can I be effective with her, or any of my students? What do they need from me? How do I build a confidence in them as creative, problem-solving people?

Over time, I have learned to teach to the individual rather than the music. Each is like an intricate puzzle I have to solve. I am constantly finding new ways of bending my teaching to the particular child’s mind – testing and twisting my knowledge.

I separate the reading process from the playing process, giving them difficult, fun pieces to play where the note heads are converted to letters. Their note-reading books are graphically colorful, spacious books.

I point out that speed (so well rewarded in our society) is intrinsically of little value. A completed job well done, regardless of time, is a win. I catalog, articulate and trust their abilities, reminding them occasionally that we are working together on their weaker points. I encourage them to think of alternative solutions – there is rarely one approach to a problem.

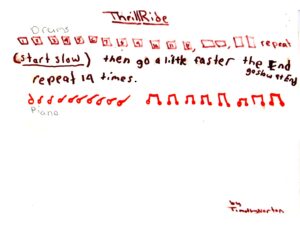

Most importantly, I give them opportunities to experience and claim their own creativity. They are constantly composing music, either at home or in their lesson, notating it as they please. And several times a year, I gather them together in informal settings to perform and celebrate their efforts.

Most importantly, I give them opportunities to experience and claim their own creativity. They are constantly composing music, either at home or in their lesson, notating it as they please. And several times a year, I gather them together in informal settings to perform and celebrate their efforts.

I talk less. Give them time to solve problems without jumping in with answers. Have rests.Do lots of stickers (even for my teenagers), and work on my own patience.

Patience, patience. The child will not be baked until their mid-20’s, sometimes older. I am in it for the long run. I value the children’s excitement rather than their abilities. And I put myself constantly be in a position to say yes. Yes, yes. Why not?

Listen! Tremble for violin, cello and piano

A few days up at the Charles Ives Center for the Performing Arts gives me relief. I am in residence with musician, composer, and maverick

A few days up at the Charles Ives Center for the Performing Arts gives me relief. I am in residence with musician, composer, and maverick  piece is a voyage of technical manipulations involving tape delay and difference tones – those haunting resonances that appear when certain pitches rub against each other.

piece is a voyage of technical manipulations involving tape delay and difference tones – those haunting resonances that appear when certain pitches rub against each other. My three-year residency in Delaware is winding down. We sit in meetings and talk about outcomes or measurable results of my work in community settings.

My three-year residency in Delaware is winding down. We sit in meetings and talk about outcomes or measurable results of my work in community settings. because I trust it will take root in some strange and unimagined way, in its own time. I teach as an act of faith; a spiritual practice. I get up every day, and do it. “Here,” I say, “this is what I have for you today.”

because I trust it will take root in some strange and unimagined way, in its own time. I teach as an act of faith; a spiritual practice. I get up every day, and do it. “Here,” I say, “this is what I have for you today.” Timothy stands close to me. When I move, he moves. He waits for me to play his piece with him and follows me like a shadow around the room.

Timothy stands close to me. When I move, he moves. He waits for me to play his piece with him and follows me like a shadow around the room. have no composition. I stall, thinking.

have no composition. I stall, thinking.

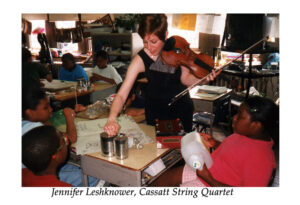

Listen: Render, for string quartet was commissioned for the Cassatt String Quartet

Listen: Render, for string quartet was commissioned for the Cassatt String Quartet