Ownership of music

My years of experience in community settings has brought me to understand that engaging the public, especially children, is much more than talking to or performing for them. It is about bringing them into the heart of musical experience and giving them ownership of music – a long and resounding affirmative. Yes, you can compose (without years of study). Yes, you can perform with professionals; I will write those pieces for you.

During a three-year residency at the I have my first opportunity to create a work that included students performing with professionals.

I write Paper, Glass, String & Wood for three quartets, one professional and two student quartets of different abilities.

I ‘telescope’ the piece – providing multiple performance possibilities: for professional quartet and two or three quartets, or for professional string quartet and student string orchestra.

The musicians rehearse the new work in the dark sanctuary space of the Fleisher Art Memorial. Eight students from area high schools join the professional performers made up of members from the Philadelphia Orchestra. The students are quiet and wide-eyed.

There is an ebb and flow to the rehearsal. The cellist lifts his head and cues the violinist with a smile. At an intonation problem, the quartet plays the offending section at a snail’s pace, checking the tuning. The first violinist leans back to the student quartet and asked them how they were rubbing the strings to produce a sound effect in their parts.

What is it when you share these moments? The total is always much more than the sum of the notes. It being able to be in the energy and joy of playing together while discovering a new work. It is being able to directly experience how musicians, like a magical school of fish, move through the music, bending and nodding at each other, smiling, adjusting, and pausing; both individuals and community at the same time.

The young musicians are rapt, shy and curious. They ask me questions, and wonder out loud. Being a professional musician is no longer an abstract concept; they now can feel and smell it. Standing close to me while the quartet practices alone, one of them whispers, “I never thought I would go into music as a profession, and now…” his voice trails off.

So many possibilities in that “and now.”

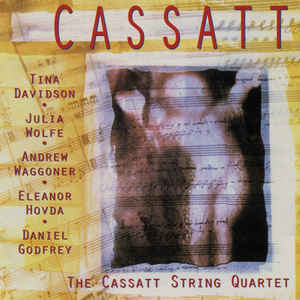

Paper, Glass, String & Wood is recorded by the Cassatt Quartet on Albany Records.

Tina Davidson: It Is My Heart Singing